For my 50th post and my one-year anniversary on Wordpress, I'd like to share what I've been up to these last few weeks.

Two years ago, I was forwarded an email from someone in Germany whose father had spent time in Canada during the Second World War as a prisoner of war. Lutz, the sender of the email, knew that his father had spent time at a camp in Manitoba but wasn't sure about his exact whereabouts. A quick search of my records provided some insight into the life of Lutz's father, Richard.

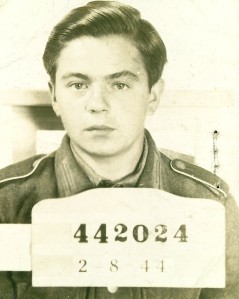

|

| Richard Beranek after his capture in June 1944. |

Less than a month after his capture, Richard found himself aboard the Empress of Scotland en route to Halifax. Once the ship docked, Richard and 1,000 of his countrymen began the four-day journey to Camp 132 at Medicine Hat, Alberta.

In the early summer of 1945, Richard was once again loaded onto a train across the Canadian, prairies. This time, however, he was one of 100 PoWs destined for the farming project at Grassmere, Manitoba. The Grassmere Farming Project was located just north of Winnipeg and began its life in the 1930s as a relief project. By 1945, the buildings were vacant and were converted to be used as a makeshift prisoner of war camp. From June to November, Richard had his comrades worked on the local beet fields, assisting local farmers who needed extra labour.

|

| PoWs at Mafeking, Manitoba. |

At its peak, the Mafeking camp employed 130 PoWs and served as a wood-cutting camp for the Manitoba Paper Co. Throughout the winter, PoWs would cut and then haul wood to Mafeking, where it was then loaded onto trains to take it to the mill at Pine Falls. While it is unknown whether Richard worked as a woodcutter or a hauler and loader, he did enjoy his time working in the Canadian bush.

His time here, however, was brief, for in April 1946, the entire complement of the camp was transferred to Camp 23 at Monteith, Ontario and then repatriated back to Britain. Richard eventually made his way back to Germany in 1947 where he remained until he passed away in 1988. While he never had a chance to return to Canada, he fondly recalled his time here as the best years of his life.

|

| Lutz at Grassmere. |

A week later, Ed Stozek had arranged for us to take two wagons out to the site of the Riding Mountain Park Labour Project (also known as the Whitewater Prisoner of War Camp) in Riding Mountain National Park. Fortunately the weather cooperated (mostly) and the day was spent exploring the site.

|

| The Beraneks and Ed Stozek looking at Whitewater Lake in Riding Mountain National Park. |

Last week, we visited the camp at Mafeking. With the assistance of a local, Delbert, who, at the age of six, met some of the PoWs, we toured around the sites inhabited and worked by Richard and his comrades. Like so many of the PoW camps in Canada, little is left of the site today. That being said, we were still able to find some of the log cabins built by the PoWs and various pieces of debris scattered throughout the site. Seventy years later, the Beraneks had returned to Mafeking.

|

| The Beraneks exploring the remnants of a truck at Mafeking. |

When I first received Lutz's email, I was certainly not expecting to be a part of experience such as this one. I feel extremely privileged to be able to be part of the Beranek's journey and to be able to help fill in some of the gaps of Richard's time in Canada.

It isn't everyday that you are able to take a family and show them where their father lived and worked seventy years ago...

Note: For more of Lutz's journey, you can read Bill Redekop's article in the Winnipeg Free Press (link)